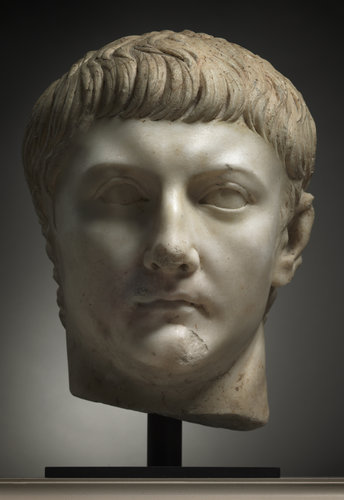

Collecting antiquities can cause headaches even for the big guys. The Cleveland Museum of Art recently purchased a stunning marble portrait from around the time of Christ thought to be that of Drusus Minor, son of the Roman Emperor Tiberiu, and a beautifully preserved Mayan cylinder vessel with a painted battle scene from A.D. 600-900.

In the process, the Cleveland Museum jumped into a firestorm in the world of fine art between American and other modern western nation museums, and the countries from which the antiquities originated. Frequently, the countries of origin argue that the works are vital pieces of cultural heritage which were illegally taken from their soil. It doesn’t help the owner’s side of the dispute when, frequently, the antiquities have huge gaps in provenance and title/ownership.

Further, changing values and mores, have resulted is a shift in the dynamic. In decades past, the inclination was not to pursue those who purchased antiquities without knowledge of the theft. Perhaps, the development of holocaust art case law has shifted that dynamic in the fine art market. The victim is no longer the sympathetic defrauded holocaust family. Now, countries of origin draw sympathy from the same well created by holocaust fine art disputes. Countries of origin have achieved some success using similar arguments, to wit, that their antiquities were looted natinal treasures, no matter the good faith of the current owner or how long ago the theft occurred.